meet Mongabay host

Romi Castagnino

Romi Castagnino is a Peruvian conservation biologist, wildlife photographer, filmmaker, and science communicator based in Australia. She has conducted research in the Amazon Rainforest and tropical montane cloud forests of Peru using camera traps to study carnivore conservation. Romi hosts Candid Animal Cam for Mongabay.

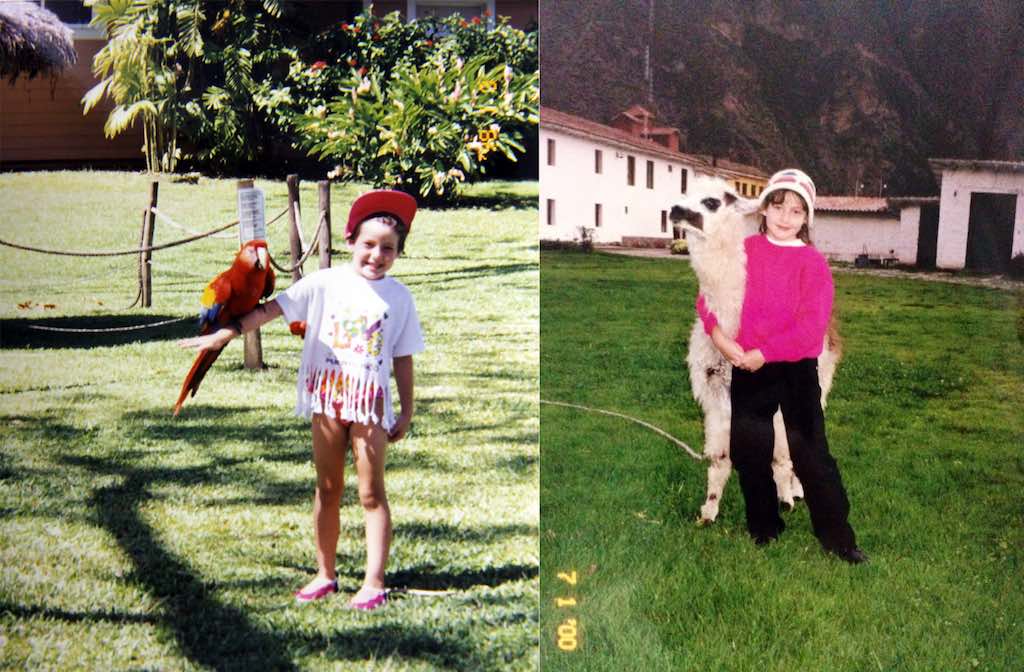

Mongabay Kids: How did you become interested in nature and wildlife? Did you spend much time in nature as a kid?

Romi: As a kid, I’ve always loved being outdoors, either walking in nature, playing sports or camping.

I took my Dad’s film camera everywhere to try and get a snap of any animal I could see … I remember I was fascinated by a pair of red-backed hawks that would visit the park next to my house!

Growing up I was fortunate that my parents took me and my sister traveling around Peru which sparked my curiosity beyond my local wildlife. That curiosity was amplified when I started watching Animal Planet and National Geographic Channel every day after school.

I dreamed of traveling to the places I saw on TV and searching for animals like Steve Irwin and Jeff Corwin did.

I have to thank my sister for giving me a sense of responsibility around environmental issues from a young age.

When I was six she had the brilliant idea to start an environmental club with me and my cousins called Save The Planet. We would organize beach cleanups and perform dance shows to raise money for charities, we had a great time!

Now that I look back, what a blessing to have someone I looked up to tell me I could make a positive impact no matter my age.

Mongabay Kids: When did you decide that you wanted to become a biologist? What steps did you take to make that happen?

Romi: As part of my high school biology class, we took a trip to the Amazon Rainforest which made me fall in love with the natural world.

We learned how the ecosystem worked, how to identify animal tracks and all about the Amazonian species’ biology. That trip made me want to study nature and wildlife even more than before.

At the time, my favorite subject at school was geography so I decided to pursue Geography and Environmental Studies at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. The career allowed me to travel throughout the country and learn from communities working in conservation.

During those years, I decided I wanted to specialize in wildlife biology and because my degree didn’t offer the science courses I needed, I studied a semester abroad at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The program allowed me to volunteer in different organizations to gain skills as a field biologist.

After graduation, I started to invest more time improving my skills in photography and filmmaking, my other passions. I also started working for Mongabay where I learned from extraordinary environmental journalists all about science communication.

A year later I moved to Australia to study a Masters in Conservation Biology at The University of Queensland. And now after graduating, I’m able to bring my academic background and science communication skills into my work in Mongabay.

Mongabay Kids: You have done some interesting research in the Peruvian rainforest. Can you tell us about the rainforest that you worked in? Where is the forest and what are some of the species that live there?

Romi: I’ve done research in both the Amazon Rainforest and the Tropical Montane Cloud Forests of Peru. Both ecosystems are magical.

The Amazon Rainforest is a sensory experience like no other. You are surrounded by wild sounds 24/7.

The first day you arrive in the Amazon you can really feel the humidity but then your body gets used to it … there is so much to explore that you forget about it pretty fast.

To get to the field station you have to travel through majestic meandering rivers by a motorized canoe called peque-peque.

Sometimes you can see families of capybaras on the river banks. (Capybaras are the biggest rodents in the world!) Besides fascinating bugs, monkeys and birds, if you are really lucky you’ll get to see wild cats like jaguars, pumas and ocelots.

And I also have to mention one of my favorite things to look for in the rainforest: fungi! There are so many different species and some of them even glow in the dark.

I’ve also done research on the tropical montane cloud forests, which are one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth.

Due to its location, it’s a great hotspot for endemism, this means that many animals only live there and nowhere else in the world like the endangered mountain tapir and the beautiful Andean cock-of-the-rock.

Also you get to see different types of forests when you go up in elevation; you can go from moss-ridden forests to paramo (a plateau above the tree-line covered with shrubs and grasses).

My favorite species that live in these forests are the spectacled bear and the South American coati.

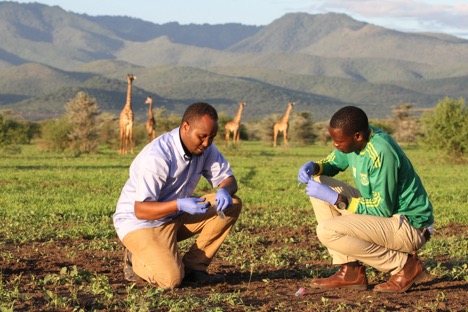

Mongabay Kids: What was the question that you were researching for your project in the forest? What are camera traps, and how did you use the information from them to answer your research question?

Romi: Camera traps are devices that are triggered by an infrared sensor when body heat or movement from an animal is detected. They offer a cost-effective and non-invasive tool to monitor elusive wildlife.

In my most recent study, I used camera traps to assess how a dirt road located in the periphery of a national sanctuary affected the distribution and behavior of 11 carnivore mammals (including species like the puma, spectacled bear and the Andean fox).

The study site was located in the cloud forests of The Tabaconas Namballe National Sanctuary in Peru.

By analyzing the species’ spatial (in space) and temporal (in time) activity patterns I was able to find, for example, that more than half the species avoided the road.

Knowing which and how species alter their movements due to the presence of human development is crucial to design mitigation plans that will help protect the animals and their habitat.

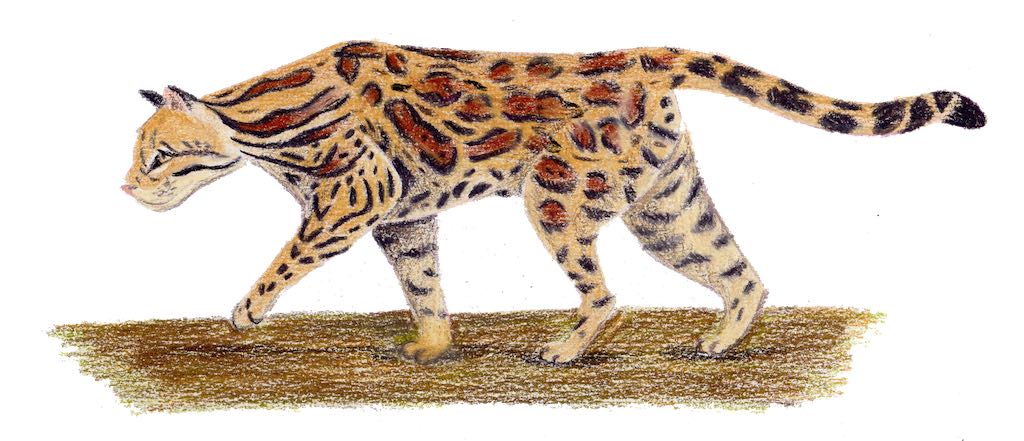

In another study, I used camera traps to assess how tourism affected the presence of ocelots in Amazonian forests. For it, I had to identify individual animals.

Ocelots, like many other felids, have spots that are unique to each individual, much like human fingerprints, so biologists use their markings to identify individual animals from camera trap photos and videos.

After analyzing the data, I found that the ocelot population surrounding my study site was one of the most abundant (meaning that there were many ocelots) across the species’ distribution range. I also used the study’s findings to suggest recommendations for ecotourism management plans.

Mongabay Kids: You are now using information from camera traps around the world to help people learn about how cool animals are. Can you tell us how you do that?

Romi: Camera traps are a fantastic tool for science and conservation. A lot of animals are elusive and will do their best to avoid being seen, so camera traps offer you the possibility of peeking into the secret life of animals in their natural habitat.

Researchers put a lot of effort into setting up camera traps in the wild to gather important biological and ecological information and sometimes the videos and photos taken by the camera traps just end up stored on external drives.

Rhett Butler, Mongabay’s founder, had the fantastic idea to start a digital series showing animal’s behavior using footage from camera traps, that way we would repurpose footage and get people closer to nature.

Candid Animal Cam has now over 100 videos in English and Spanish and we’ve built collaborations with scientists and organizations from every corner of the world that strive to protect our planet and the creatures that live in it.

Mongabay Kids: What advice do you have for young people who are interested in becoming biologists, but aren’t sure how to get started?

Romi: It can be a bit overwhelming choosing what to study so my advice is to expose yourself to as many opportunities as possible.

That could be attending workshops, taking online classes, watching online seminars (many organizations are now live streaming them for free), or volunteering at your local wildlife center.

That is the best way to meet like-minded people that can help you decide what path to follow.

And also, don’t be afraid to reach out to biologists on social media, many friendly biologists would be happy to share their journey and answer your questions about the field.