G

is for George, giraffe & genetics!

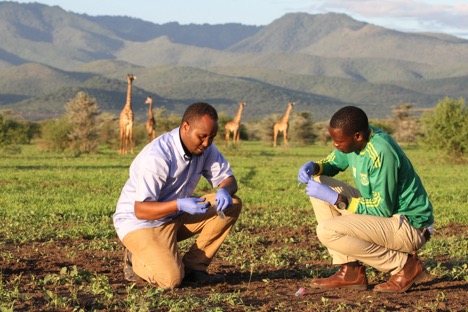

Meet

George Lohay

Dr. George Lohay is a biologist studying Masai giraffes in Tanzania. George loves wildlife and plants. George has also worked with elephants, lions, and geckos. George’s current research focuses on using genetics to help conserve giraffes.

George explains why he likes giraffes and what conservation challenges they face:

“Giraffes are the most beautiful animals. They are browsers, meaning they eat leaves particularly from acacia plants. Cutting down trees for human settlement and activities such as farming reduce giraffe’s habitat. Also, as human populations increase there will an increase in illegal hunting of giraffes which affects their population.”

Masai giraffes live in Kenya and Tanzania. There may be more Masai giraffes than other kinds of giraffes in Africa, but this does not mean that they are safe. George explains why that is:

“Recently, Masai giraffes have been listed as endangered species because their number declined by 50% just in 30 years. The current estimated number of Masai giraffes is 35,000. While this number looks great, if we do not protect them in a few years their number may even go further down.”

George and his colleagues use genetics to study the gene flow between giraffe populations in Tanzania.

Tanzania is in East Africa

Dig deeper: genetics

Genetics is the science of understanding DNA, the blueprints in our cells that carry all of the information that makes an organism – an individual animal.

The parts of the DNA that store this information are called genes.

Gene flow is the measurement of how genes in organisms move between populations – or groups – of the organisms.

George explains why genetic diversity is important for giraffes: “To maintain a healthy giraffe population, there should be an exchange of genetic material to produce variation. Genetic diversity is good for the conservation of species. When a population is isolated for a long time, there is a danger of an increase in inbreeding – mating between closely related individuals – that may lead to an extinction of species. We love giraffes and other wildlife so we do not want extinction to happen.”

How will the research on gene flow between giraffes populations be used to help protect them?

“This research is important because we want to understand how human activities such as livestock keeping, farming and infrastructure building have affected movement of giraffes and hence gene flow. We advocate for protecting migratory routes – wildlife corridors – used by wildlife to move between protected areas. We will use our results to show people the impact of isolated habitats. We hope to secure wildlife corridors in Tanzania to facilitate movement of giraffes and other species,” says George.

How did George become interested in being a scientist and researching questions like measuring the gene flow between Masai giraffe populations?

“I became interested in doing wildlife research immediately after completing high school in Tanzania. After our high school graduation, we were offered a trip to visit a national park in northern Tanzania. After that trip all I wanted was to be a conservationist and an ecologist.

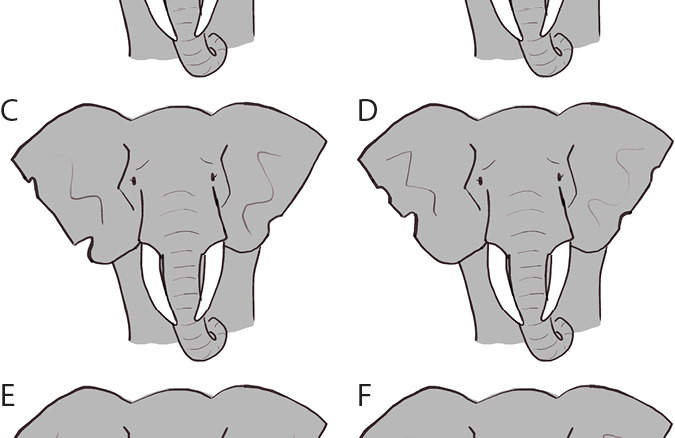

I have worked on several species like yellow-headed dwarf geckos, lions, elephants, and now giraffes. I love plants too, so do not be surprised to see me doing research on plants in a few years to come.”

George offers this advice for young people who want to be scientists and help protect animals like he does:

“Study hard, love what you do and treat others well – including plants and animals!”