By Megan Strauss

A few months ago, I found myself glued to a live stream, anticipating the birth of a litter of pups. I checked in every couple of days, morning and night. I was not waiting for golden retrievers or Labradoodles — I was waiting for a slithering pile of baby rattlesnakes. I was watching Project RattleCam.

Professor Emily Taylor co-founded Project RattleCam in 2020. Emily is a reptile expert who wants to reveal rattlesnakes’ secret lives and help show their gentle nature to the world. Emily and her team use cameras to monitor rattlesnake behavior. They observe what the rattlesnakes eat and the predators they face. They also record when the babies are born, how the snakes parent, and other snaky behaviors.

This year, the cameras were pointed at two dens in Colorado and California from early summer through October. Dens (also called rookeries) are where the snakes gather to mate, give birth, and care for their young. The Colorado RattleCam focuses on a mega den of about 2000 snakes and is on 24/7 thanks to built-in infrared tech. (Learn about the RattleCam tech here.)

Unlike most snakes, rattlesnakes don’t lay eggs. They give birth to live young, known as pups. The cameras are there to capture all the action!

After tuning into the Colorado RattleCam, I had many questions. For starters, do the cameras bother the snakes? Snake researcher Owen Bachhuber reassured me, saying, “The cameras do make a slight noise when they move, and the snakes can see them moving. They seem to continue with their lives like nobody’s watching, though.”

When would the first babies be born? This year, the first pups emerged on August 22. According to the Project RattleCam FAQ page, western and prairie rattlesnakes typically give birth to about eight babies.

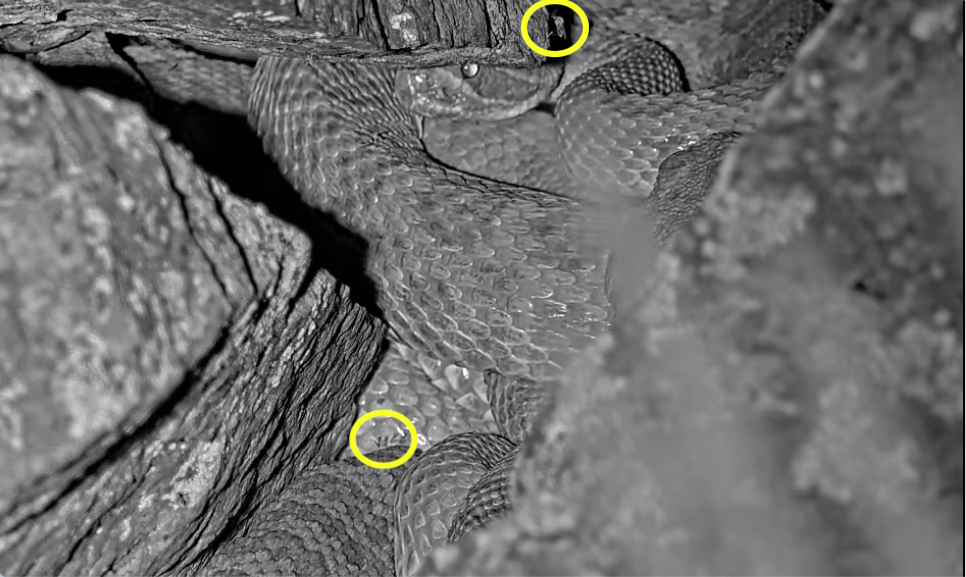

August 29: I took this screenshot of pups cuddled up with an adult at the Colorado cam site. Look at those beautiful babies!

At night, I noticed little insects (circled in yellow) flitting around and landing on the snakes. Were they flies? Or maybe mosquitoes pestering the snakes?

According to Owen: “The insects you saw are flies in the family Psychodidae. We have seen some females feeding on the snakes’ blood. Most of the flies we see are males, which may be trying to find mates.”

Owen shared a video of the “flies dancing on the snakes.”

Rebranding rattlesnakes

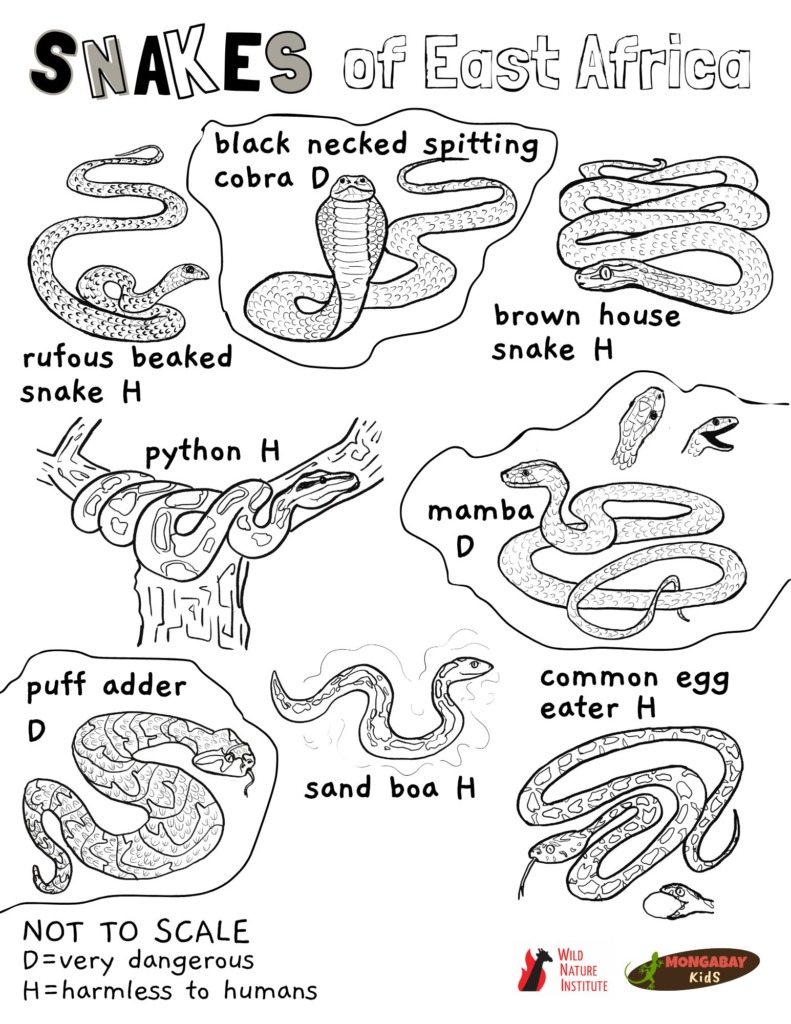

Artist Mike Essa created this adorable project logo featuring a mother snake and her young. Look closely at the tail tips of these pups. They start life with a “button.” New rattle segments are added as the babies grow and shed their skin.

Owen and the team at Project RattleCam want us to understand that “Rattlesnakes are elegant, fascinating, and important for the environment. The more we learn about them, the more we love them.”

I couldn’t agree more. As a field biologist in rattlesnake country, I developed a healthy respect for rattlers, often nestled under the sagebrush. I learned to give them space. Watching RattleCam live has given me a new appreciation for these snakes and their complex social lives.

Now that the rattlesnakes are hibernating, the cameras have been turned off. However, I know I will return when the next Northern Hemisphere summer rolls around. I will eagerly await the new pups to debut on camera. I encourage you to tune in then, too.

For anyone keen to learn more about rattlesnakes, the project RattleCam website is a must-visit destination. You will find answers to your questions about rattlesnake natural history, the project tech, and more. You can also meet individual snakes, recognized by their unique skin markings.

Rattlesnake citizen science!

For kids, families, and school classes that want to get involved, check out the opportunities to name a snake and submit interesting things you’ve spotted on the live stream.

Learn More

The Project RattleCam livestream was created by scientists from Cal Poly, Central Coast Snake Services, and Dickinson College with help from Donors. Professor Emily Taylor and Associate Professor Scott Boback co-founded Project RattleCam. Owen Bachhuber, interviewed for this story, is a graduate student at California Polytechnic State University.

Last updated: 29 March, 2025