Doug Beetle chats with:

Lemur researcher

Stephanie Canington

Image: Stephanie Canington

Stephanie Canington studies the feeding behavior of ring-tailed lemurs at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland. Stephanie has conducted research at the Duke Lemur Center in North Carolina and at St. Catherines Island, an island in the US with a population of free ranging ring-tailed lemurs. Stephanie has also previously worked at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum. She is a volunteer with the Lemur Conservation Network.

Please tell us about ring-tailed lemurs, Stephanie!

Doug Beetle: Introduce us to the ring-tailed lemur. Is it related to monkeys? Its tail looks like a racoon tail – is it related to raccoons?

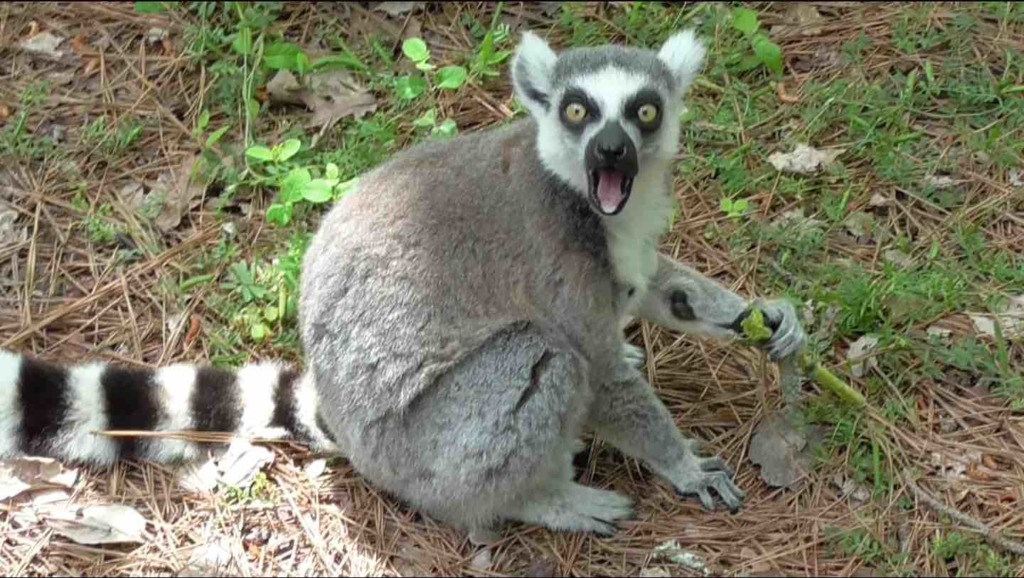

Stephanie: The ring-tailed lemur is a type of primate called a “strepsirrhine.” Unlike our noses (or the noses of monkeys and apes), strepsirrhines have wet noses – like your dog or cat! Even though strepsirrhines have smaller brains than monkeys or apes, they have a longer nose with a much better sense of smell! Other strepsirrhines include lorises and galagos.

Ring-tailed lemurs spend more time on the ground than any other species of lemur, although they are great climbers, jumpers, and even sleep in trees! They are about the size of a cat and have a long tail with black and white rings. Even though the striped tail is an easy way to identify them among other lemurs, they aren’t the only animals to have them. Many animals share similar features! Ring-tailed lemurs, raccoons, ringtailed cats, and even red pandas all have striped tails, even though they aren’t closely related.

Lemurs also have a unique tooth feature – their bottom front teeth are pushed together and point outwards in the shape of a shovel. This is called a “toothcomb” and it’s used for grooming themselves and other members of the group!

Doug Beetle: Where do ring-tailed lemurs live? Do they live in family groups?

Stephanie: In the wild, ring-tailed lemurs are only found in the southern half of the island of Madagascar. However, they are the most common species of primate found in zoos! Family groups are called “troops” and there may be as many as 30 members.

Doug Beetle: What do ring-tailed lemurs eat?

Stephanie: They eat MANY different things. Although they LOVE fruit, they eat leaves, flowers, bark from trees, insects, and even dirt! Ring-tailed lemurs are a type of “seed disperser” in Madagascar. Sometimes, when they eat the seeds of fruits, the seeds survive the passage through the lemur’s body and end up in the lemur’s droppings! The seeds can then grow from the lemur’s droppings and become new trees!

Doug Beetle: What questions are you asking about ring-tailed lemurs with your research? What do you hope to learn about them?

Stephanie: My research is about lemurs in wild and captive (or, human-maintained) habitats. There are many types of human-maintained habitats, including zoos. There are also places (like the Duke Lemur Center) where lemurs have access to live in the forest for most of the year (coming inside when it’s cold). There are places like St. Catherines Island, an island closed to the public and used for conservation, where lemurs have access to the whole island! The key though, is that the lemurs in human-maintained habitats have access to veterinary care and are provided with meals.

I study what ring-tailed lemurs eat and how they eat it. Do lemurs that live in captive habitats have feeding behaviors similar to those living in the wild of Madagascar? Do they eat foods of different nutritional or mechanical challenge? For example, do the fruits fed to lemurs in zoos have more sugar than the fruits they eat in the wild? Are they easier to eat (for instance, are they softer)?

I also study the history of zoos and how and when lemurs first left Madagascar on ships to Europe and the United States.

Doug Beetle: How are you answering your research questions? Are you mainly watching lemurs in the wild? Are you doing experiments in a laboratory?

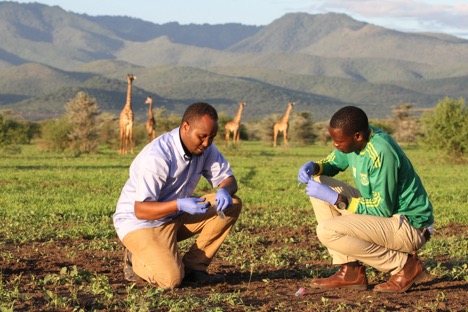

Stephanie: I use four strategies to answer my research questions: zoo studies, fieldwork, lab work, and diving into the historical records.

Live animal research

For part of my research, I filmed ring-tailed lemurs at the Maryland Zoo while they were eating – watching what food items they were selecting, in what order they selected it, and for how long they ate! I also conduct fieldwork at two places in the United States – the Duke Lemur Center and on St. Catherines Island – a small island off the coast of Savannah, Georgia.

I select a focal animal to follow all day and film him or her every two minutes for two minutes throughout the day to study their activity patters. I identify species of plants they eat and what parts they prefer.

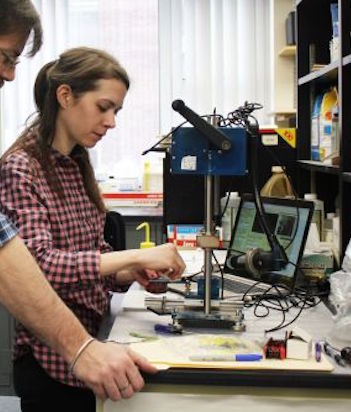

Lab work

I use a special machine (called a Lucas Scientific FLS-1 tester) to test the mechanical challenge of foods that lemurs eat. Specifically, I’m looking at the “toughness” of a food. When you put a piece of food in your mouth, without even thinking about it, you’re using your teeth as tools to “process” the item. The item sits on your bottom teeth and your upper teeth come down to either puncture the food (like pushing a plastic straw into a juice box) or shear the food (grinding the food back and forth, like a cow).

The amount of force it takes to make the food item crack and start to break apart can teach us about how much an animal has to “work” to eat. Imagine the difference between eating a bunch of gummy bears versus eating a banana! It takes lots of chews for the gummy bears to break down, yet very little “work” goes into eating the banana!

Historical record

Finally, I study how zoos change over time. You hear all the time how animals evolve to adapt to their environments in the wild. Well, there is also an evolution of the captive habitat that has happened for hundreds of years. Now, zoos serve the purpose of education and conservation and have worked very hard to create homes for their animals that resemble their wild habitats and to feed them food that is best suited for their individual needs.

I use scientific papers, books, newspaper articles, and even artwork going back to the 1600’s to study when and how lemurs made their way into zoos and how zoos themselves have adapted to better suite the needs of the lemurs.

Doug Beetle: How are ring-tailed lemurs doing in the wild? Do they have conservation challenges?

Stephanie: Unfortunately, ring-tailed lemurs have been classified as Endangered on the IUCN red list since 2014. This means that ring-tailed lemurs are at risk of going extinct if we don’t act now.

Forest loss is the major conservation challenge for all lemurs in Madagascar. Lemurs need forests to live in, need trees to eat from, and need forest cover to safely travel. When male ring-tailed lemurs reach maturity (become adults), they leave the group they were born into and move into a new group. This is a common behavior in mammals that promotes strong genetic diversity and is critical for keeping healthy populations.

However, many areas of Madagascar are patchy forests with faming land, roads, homes, and towns separating lemur groups. The males often have trouble safely moving from one patchy forest to the next.

Lemurs are also at risk because of poaching (killing an endangered animal for food or to sell) and the pet trade (people keeping lemurs in their homes as pets).

Many organizations are working to solve these issues – especially habitat loss. You can read more about these specific organizations on the Lemur Conservation Network.

Doug Beetle: What advice do you have for young people who are interested in doing research on ring-tailed lemurs or other animals like you are?

Stephanie: The first step in doing research on an animal is learning about the animal’s behavior. Where does the animal live? What does it eat? What kind of research questions do I want to investigate? Read everything you can about the habitat, feeding ecology, and social behaviors of ring-tailed lemurs. The more you know about them, the closer you feel to them and the more informed your research questions will be!

There are TONS of online educational resources, including the Duke Lemur Center, the Lemur Conservation Network, and the Lemur Conservation Foundation.

Also, it’s never too early to get involved! Check out your local zoo for opportunities to conduct citizen science projects, sign up for educational classes or camps, and even volunteer or intern! For example, the Duke Lemur Center hosts a lemur-based summer science camp for rising 4th – 6th grade students which this year, due to COVID, was virtual:

https://lemur.duke.edu/camps-and-workshops/

Finally, don’t be afraid to reach out to lemur scientists. Many of them work with major lemur conservation organizations and you can usually find their contact info on their university websites. Many researchers have tons of field data (including videos, audio, and photos) they need help going through and are often excited to have a hand. It may seem scary at first, but don’t be afraid to express your passion for lemurs and your desire to learn about research!

Doug Beetle: What can young people do to help ring-tailed lemur conservation even if they live thousands of miles from where the lemurs live?

Stephanie: A big way to help (right from home) is by supporting and visiting accredited zoos that maintain captive lemur breeding programs or by donating to accredited not-for-profit organizations that do on-the-ground conservation work in Madagascar. You can find a list here:

https://www.lemurconservationnetwork.org/how-to-help/support-conservation/

Zoos often list ways you can help out on their websites.

You can also spread awareness about Madagascar’s habitat loss and lemur conservation efforts to your friends, family, and on social media. Awareness leads to passion and that is the key to saving these beautiful animals.

Find out more about the places I work:

Note: Mongabay Kids is not responsible for content published on external websites.