By David Brown

“People look at you blankly when you mention botos,” says wildlife biologist Dr Tony Martin.

Dolphins are famous animals. They swim through the oceans of the world, frolicking among the waves and eating fish.

The dolphins of the oceans have some much less well-known cousins: botos. Botos are a type of freshwater dolphin that lives in the Amazon River of South America.

frank wouters, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Dr Martin and his colleagues have been studying botos in Brazil for more than 20 years. He explains that little research was done on botos before this study because they live in water the color of coffee. Rotting vegetation in the Amazon makes the river water very dark.

Researchers cannot dive in the river and make close observations of the botos because they cannot see them. Watching botos from the surface is also a problem. “They emerge for only seconds and they all look alike,” explains Dr Martin.

Dr Martin’s team eventually figured out a system for telling individual dolphins apart. They catch a boto in a net and bring it up on a beach near the river. The boto is weighed and measured. A female boto is given an ultrasound to see if she is pregnant.

Before the boto is released, it is marked with a dot on its dorsal (back) fin using liquid nitrogen. This process is called freeze marking. The liquid nitrogen removes a small amount of pigment from the boto’s back, leaving a unique mark that can be used to identify the boto when it surfaces in the river.

Dr Martin and his team have identified 625 individual botos in their study population in Brazil. The purpose of their study is to understand the basic life history of the species and help its conservation. Dr Martin compares the study with painting a “biological portrait” of the species.

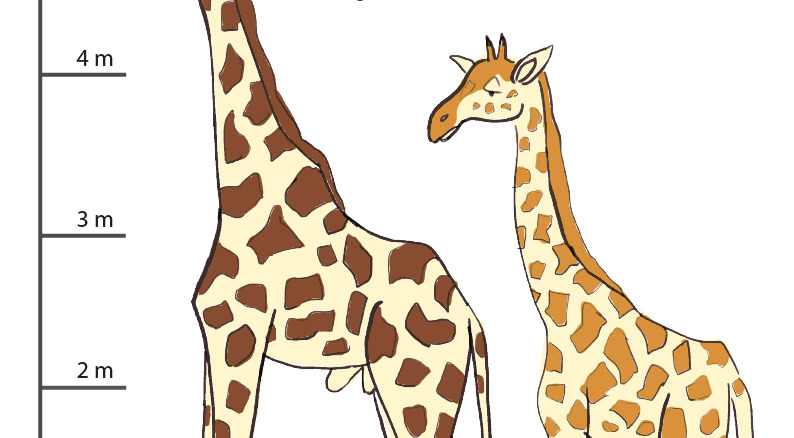

Dr Martin and his team have found that male botos are much larger and heavier than females. Males weigh up to 190 kilograms (419 pounds) and are 2.3 meters (7.5 feet) long. Females weigh 100 kilograms (220 pounds) and grow to 1.9 meters (6.2 feet) long.

For part of the year botos live in the deep channel of the Amazon River.

A river in the Amazon. Image: Rhett A. Butler

During the rainy season the Amazon River overflows its banks into the surrounding forests. These flooded areas are called igapó. Several fish species follow the floods into the igapó. They feed on the fallen fruit and seeds of the trees in the flooded forests. Botos in turn enter the igapó to eat the fish.

Flooded forest in the Amazon. Images by Rhett A. Butler

Dr Martin’s team has discovered that the social world of botos is unlike that of their marine cousins. Botos do not form groups or play and socialize with each other much like marine dolphin species do. Botos live on their own for much of their lives. Dr Martin explains that in botos, the only long-term relationship between individuals is between a mother and her baby. This bond will last between two and five years. After that the young boto will leave its mother and live on its own.

Botos are known for having pink coloration. Researchers have found that much of this pink coloration is caused by scar tissue. Male botos constantly fight with each other.

Jorge Andrade, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

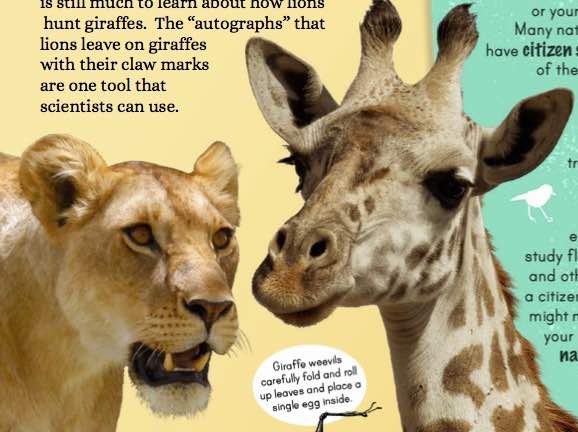

Dr Martin has documented male botos performing behavior called “object carrying”. The boto grabs an object like a stick, rock, or clump of grass and smacks it repeatedly against the water. This behavior may tell other males to stay away from the individual carrying the object.

The researchers observe that mothers and their young spend much of their time in igapó to avoid the fighting of the male botos.

Botos use sound in the form of sonar to navigate their world. The Amazon River is dark so botos rely on sonar to find food, avoid hazards like fallen trees, and find their way around their world. Dr Martin says that botos use sound like humans use their eyes.

As human populations expand into the Amazon rain forest, botos are becoming endangered in many parts of their range. Fishermen hunt botos because they see them as competing for their livelihoods. Botos drown when they are accidentally caught in fishing nets. In 2018 the boto was declared Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

“The boto is one of the world’s most unique and charismatic creatures. It has evolved over 25 million years of change on our planet. In just 100 years humans are threatening its future,” observes Dr Martin.

Dr Martin hopes that the research that his team is doing will bring attention to the plight of the botos. “It is not too late to save the boto,” he says.

An abridged version of this story is available here:

Meet the boto, dolphin of the forest!

Additional resources on botos from Mongabay.com:

https://news.mongabay.com/2018/06/hunting-fishing-causing-dramatic-decline-in-amazon-river-dolphins/