This story is about a conservation challenge from the grasslands of Nepal: how can people protect two endangered animals that share a home – tigers and hispid hares – at the same time?

What is a hispid hare?

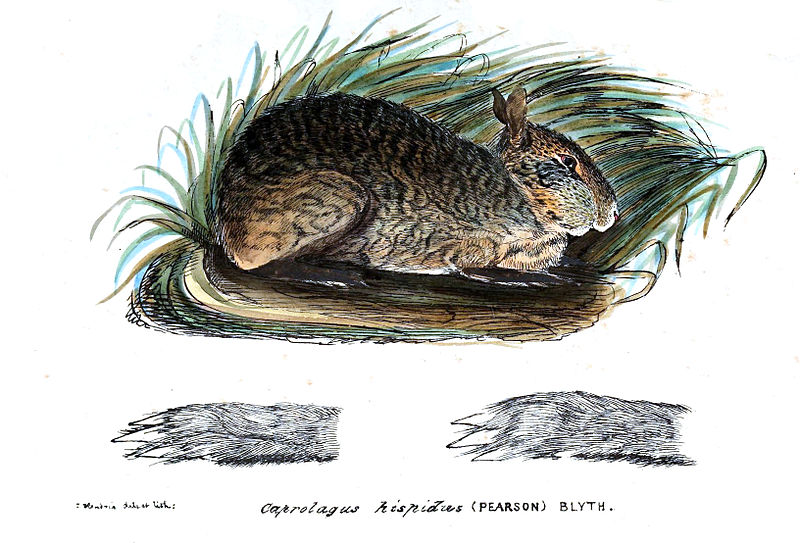

You probably know what a tiger is. But what is a hispid hare? The hispid hare is one of the world’s rarest bunnies.

The elusive, endangered hispid hare (Caprolagus hispidus) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Image courtesy of Bed Bahadur Khadka.

The nocturnal and solitary hispid hare once roamed the grasslands at the foothills of the Himalayas. The Himalayas are a mountain chain in southern Asia that has some of the world’s tallest mountains.

Not much is known about the hispid hare. Scientists thought that the hispid hare had gone extinct in 1964, but in 1966 a lone hispid hare was spotted again in the wild.

According to the IUCN, the global wildlife conservation authority, the hispid hare’s known habitat is now limited to fragmented patches of habitat in Nepal, Bhutan and the Indian states of West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, and Assam. The hispid hare possibly also lives in other parts of India and in Bangladesh.

An illustration of a hispid hare by J. Hendrie, 1845. Image courtesy of Journal of the Asiatic Society via Wikimedia Commons.

Hispid hares need dense grasslands

Hispid hares prefer dense grasslands over more open ones according to researchers. The hares use this dense grassy cover for resting, feeding, and mating.

Scientists think that the mating season of the hispid hare is in the months of January and February. Pregnant hispid hare females have been captured in those months, and other hare species also mate in January and February.

Hispid hares prefer dry earth over wet surface conditions, possibly to protect young hares from cold.

Tigers vs. hispid hares in Nepal

Wildlife conservation can be complicated. In Nepal, actions to conserve tigers may be hurting hispid hares.

Wildlife managers carry out large-scale burning of grassland habitats between February and May. They do this to help conserve tigers and their prey (like deer and antelope) that live in these grassland habitats. Burning prevents grasslands from turning into forests. Burning also helps the growth of fresh and nutritious grass sprouts that deer and antelope eat.

Officials carry out large scale burning of the Chitwan grassland habitats between February and May as a management tool. Image by Grant Eaton via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Burning may help tigers and their prey, but it could come at a cost to hispid hares. One reason is that the burning often occurs when the hispid hares are having their babies. Fire can destroy both baby hares and the dense habitat they need to grow up in.

How can conservationists help both tigers and hispid hares?

Both tigers and hispid hares are endangered. This situation shows that conserving multiple species in a shared habitat can be challenging. The burning of grasslands can help endangered tigers and their prey species, but harm other species that live in the grasslands, like the hispid hare.

Hispid hare researchers have proposed a solution. They suggest that the timing and practice of annual grassland burning should be modified to save the hares. They recommend that conservation managers burn grasslands outside of the breeding season of hispid hares. It might also help hispid hares if grasslands are not burned every year.

Grassland habitat in Chitwan National Park. Image by Peter Prokosch/GRID-Arendal via Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).