Can a salamander be as cute as a panda?

The world’s largest amphibian just might be. The Chinese giant salamander – sometimes called the “freshwater panda” – can grow to as much as a meter (over 3 feet) in length. Some have even grown as large as an adult human, at 1.8 meters long (almost 6 feet).

The species has captured the imagination of the Chinese people throughout history. The famous Taoist yin and yang symbol may have been inspired by the image of two entwined giant salamanders. The species has appeared in ancient Chinese artworks.

The yin and yang symbol

A painted vase featuring a giant salamander

The Chinese giant salamander breathes through its mottled brown, rough, wrinkled skin. It has a broad, flat head, and tiny eyes. Poor eyesight means that this large animal relies heavily on smell, touch, and the sensing of vibrations to catch prey of fish, frogs, and insects.

Female salamanders lay strings of hundreds of eggs in underwater dens which are then guarded by the male salamander. The eggs hatch a couple of months later. Measuring just 3 centimeters (1.18 inches) long when they emerge from the egg, the salamanders grow slowly to their adult size when they are about 15 years old.

The ancestors of Chinese giant salamanders first evolved in dinosaur times, about 170 million years ago. Today this salamander is an endangered species.

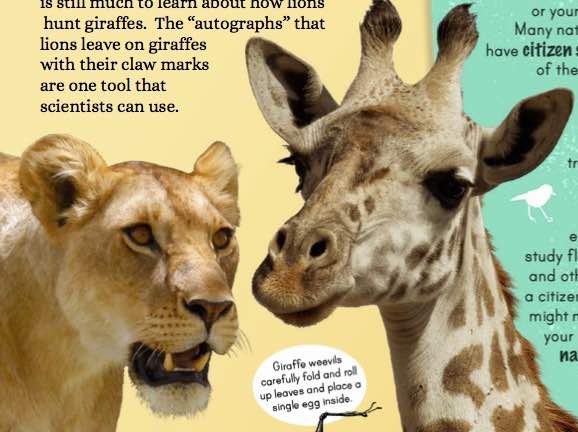

Habitat loss is one factor in the species’ decline. China is developing at such a rate that habitats, especially river systems, are being dramatically changed through sedimentation (clouding of rivers with dirt and debris), dam construction, and road construction.

In the wild an estimated 50 thousand Chinese giant salamanders live in a few fast-flowing rivers scattered across the highlands of China.

Millions more of these salamanders are grown in aquaculture (the farming of aquatic animals). The salamanders are considered a delicacy by some people.

Most of the Chinese giant salamanders on farms either came from the wild, or were hatched in captivity from wild-caught individuals. This means that there is not extensive knowledge of how to keep the species breeding in captivity.

If all of the wild Chinese giant salamanders and their habitat disappeared, then the salamander aquaculture might shut down also because the breeding population would disappear.

Conservation programs are underway to study and save wild Chinese giant salamanders, and along with them, the remaining watersheds and wild river habitats in which they live.

Salamander conservationists in China developed an educational campaign called “Go for Salamander ” with a children’s book that reached thousands of kids in schools in Guizhou province. Campaigns with museums and science centers in Yunnan and Guangxi province have reached an estimated 10,000 people.

Conservationists are working to help people understand that protection of the salamander, and its watershed habitat has a huge direct benefit to humans and other animals.

Ben Tapley is a scientist with the Zoological Society of London who is involved in conserving Chinese giant salamanders. He says, “It is important that we recognize that what is good for the Chinese giant salamander is often good for people, too!”

Learn more about Chinese giant salamanders: facts & conservation

ZSL: Chinese giant salamander conservation project

ZSL: Chinese giant salamander facts

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance: facts about the Chinese giant salamander

This story is adapted from an article by Claire Salisbury, published on Mongabay.com:

*Mongabay Kids is not responsible for content published on external sites