When Chhouk, an Asian elephant calf, was found, he was alone, underweight, and had a severe foot injury. Conservationist Nick Marx of Wildlife Alliance rescued the baby elephant. With help from the Cambodian Forestry Administration, the Cambodian School of Prosthetics and Orthotics, and an elephant named Lucky, Nick nursed Chhouk back to health and made him an artificial foot. One of the first animals to ever be fitted with a prosthetic, Chhouk helped pioneer the technology – and most importantly, was able to walk again. This true animal rescue story will satisfy animal lovers and capture the hearts of young readers everywhere.

A chat with author

Laurel Neme

Laurel Neme writes about animals for both children and adults. She contributes regularly to National Geographic and Mongabay.com, and is the author of Animal Investigators: How the World’s First Wildlife Forensics Lab is Solving Crimes and Saving Endangered Species, Orangutan Houdini, and her latest, The Elephant’s New Shoe from Scholastic. Learn more at www.LaurelNeme.com.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to illustrator Ariel Landy, Nick Marx, who wrote the foreword, Wildlife Alliance, who provided the photos, and Chhouk, who inspires me/us every day.

Doug Beetle: How did you learn about the elephant character in your book? What about this elephant made you want to tell its story?

Laurel: I learned about Chhouk over a decade ago, after he’d been rescued by Nick Marx and Wildlife Alliance. The elephant had been badly injured and needed a prosthetic foot – which is not an easy thing to make for an elephant!

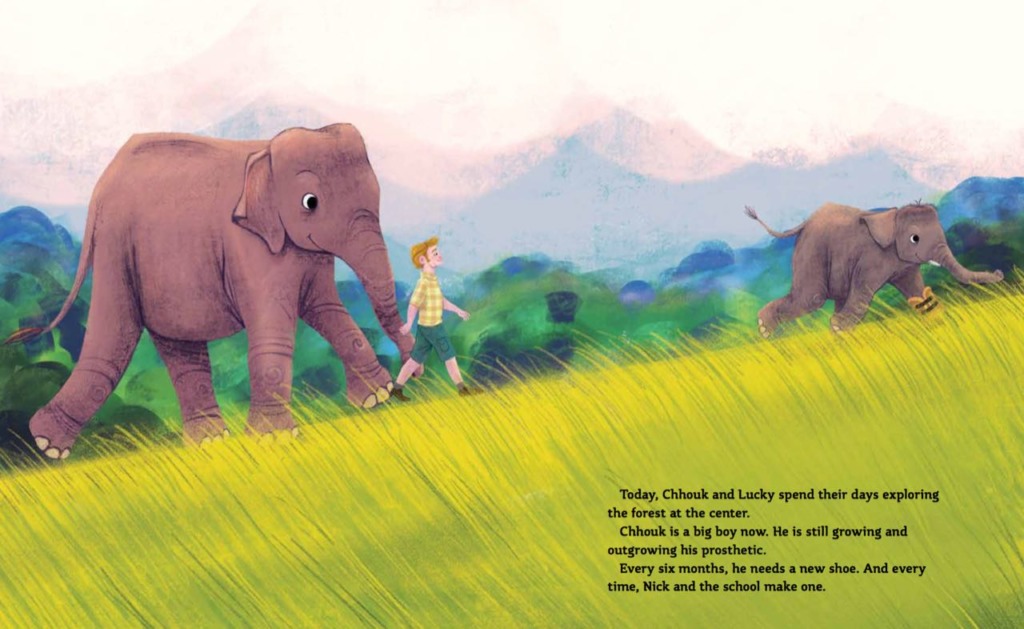

Nick helped Chhouk not only survive but thrive. Whatever problem Chhouk faced – from pain to feeling sad – Nick did everything in his power to help. I see that same “can do” attitude throughout the Phnom Tamau Wildlife Rescue Center, where Chhouk lives.

And Chhouk has it, too. In the Khmer language, “Chhouk” means lotus, which is a flower that pushes through mud to bloom. It’s a powerful symbol of triumph over hardship – and that seems to fit Chhouk perfectly. Nick often says that Chhouk’s fighting spirit is what helped him push through bad times and adapt to his new leg.

I like to think that we all can have a little bit of Nick and Chhouk inside us – and it’s why I wanted to tell this story.

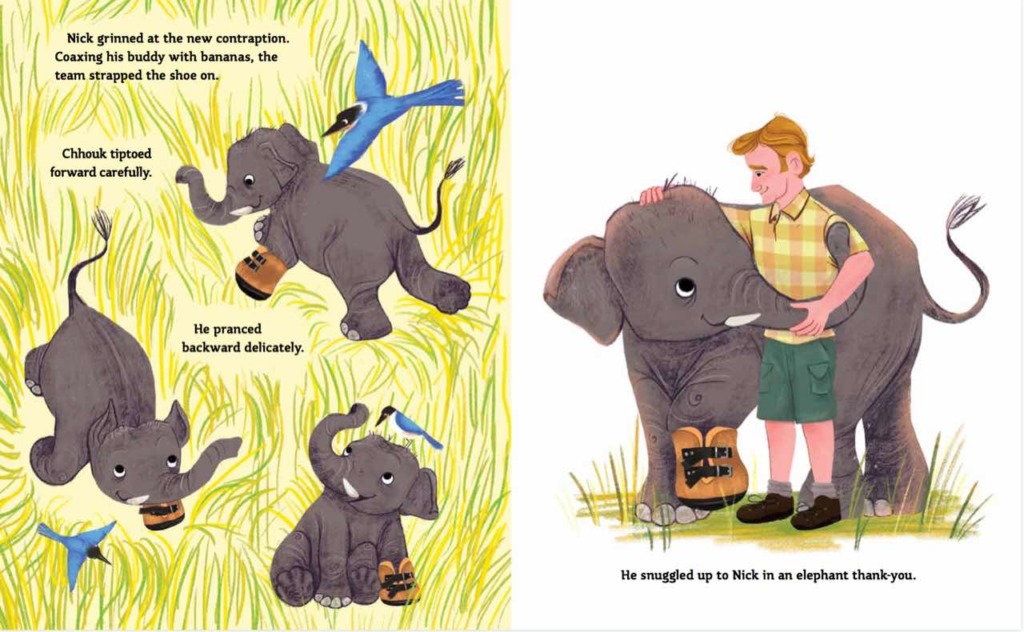

From the book:

Doug Beetle: How are the wild Asian elephants in Cambodia doing? What are the challenges to their survival? What are people doing to help conserve the elephants and their habitat?

Laurel: Cambodia has between 400 to 600 wild elephants, with most either in Mondulkiri Province in the east, where Chhouk was found, or the Cardamom Mountains in the southwest. The Cardamoms are a big virgin rainforest that’s home not just to Asian elephants but other endangered species like pangolins, sun bears, and gibbons.

Much of the land used by elephants and other animals has been cleared or fragmented by illegal logging and industrial agriculture.

Poaching is a problem too, especially from snares. Snares are simple traps made of wire or other materials that hunters use to catch food. But they can trap and hurt other animals, like tigers and elephants. It’s likely what happened to Chhouk. Snares are a big problem. Just in the month of February 2021, rangers at one outpost in the Central Cardamom mountains confiscated over 600 snares.

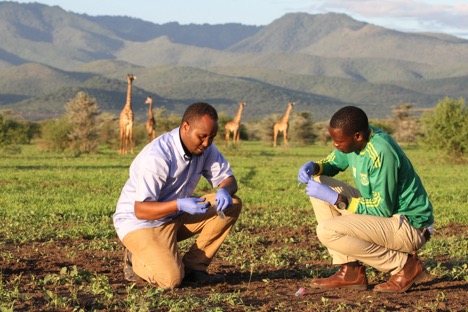

Thankfully, organizations like Wildlife Alliance and others are helping. They work to protect elephant landscapes, support ranger patrols, and help local communities find ways to earn money that conserve and don’t hurt the forest, like eco-tourism and better methods for growing crops.

Doug Beetle: What are some ways that young people can help conserve wild Asian elephants and their habitat, both kids that live in countries with elephants and kids that live thousands of miles from wild elephants, but still want to help them?

Laurel: Kids can help elephants, or other creatures, in many ways and from wherever they live.

You can start by learning about them and then sharing why you like elephants with family and friends. It could be through a project at school, in a conversation at lunch, or with a drawing.

You can even write a letter to the local newspaper. When people hear why you think elephants are special, they may start to like them too and then share that with others.

You can also support organizations that help elephants. Perhaps raise money with a bake sale or by selling note cards. Every time you sell a cupcake or someone looks at your note card, they learn why you are doing this and it helps expand love for elephants in your community.

You can also try to organize. You can start petitions or hold marches and demonstrations. Kids all over the world – from Hong Kong to the state of Vermont in the United States – have done this and been instrumental at building support for new laws to ban the sale of ivory where they live.

The bottom line is that when someone cares, they want to help protect them. And everyone can do something to help that grow.

Art activity

"Chhouk" means lotus

Suggested activity: draw or paint a lotus flower; search the Internet to learn more about the lotus plant and see examples of some spectacular flowers!

Image credit: T.Voekler, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Doug Beetle: In The Elephant’s New Shoe you write about Asian elephants. Have you written about African elephants also? As a writer, what differences and similarities have you learned about between the elephant species?

Laurel: Yes, I write about both. While African and Asian elephants may look a bit different, they face many similar threats – poaching, habitat loss, and coming into more conflict with people because their habitat is disappearing or their migratory routes are cut off from things like roads, logging, agriculture, or mining.

But there are differences, too. There are fewer wild Asian elephants – perhaps 35,000 – and they tend to live in isolated pockets. That makes habitat fragmentation an even bigger problem.

Also, domesticated Asian elephants are used in the tourist industry or for logging. While numbers are declining, there are issues of how the animals are treated and also of unemployment for the elephants and their mahouts, or handlers.

Yet all elephants play an important role in their ecosystem. They act as “gardeners” and disperse seeds, make paths for other animals, and even create watering holes. They have deep social bonds and family structures and they’re highly caring and sensitive animals, just like people!

Doug Beetle: When did you know that you wanted to be a writer? What steps did you take to make that happen?

Laurel: I’ve always loved writing and telling stories, but never imagined I’d be a writer. So I felt really lucky when my first book, Animal Investigators, on wildlife forensics, was published in 2009.

Afterwards, I saw how it had a big impact. It made people aware of the illegal wildlife trade also made them interested in science. I loved when kids would come up to me after I did presentations at zoos or schools and tell me how I changed their view of chemistry or biology because before they didn’t know why it mattered and now they saw how it could help animals.

As to how I made that happen – it was a process, and still is. Typically, I hear about something that captures my attention and imagination, and I just have to learn more. I can’t help myself.

And then, when I learn more, I end up finding it even more interesting and want to share it with others. That’s what happened with The Elephant’s New Shoe.

Doug Beetle: What advice do you have for young people who want to write about animals like you do, but may not be sure how to get started?

Laurel: My advice is simple – write!