In 1897, scientists on an expedition to Madagascar collected an interesting giant millipede. They named it Spirostreptus sculptus and entered it into the scientific record. And then, poof, science lost sight of Spirostreptus sculptus for over 120 years. Until now.

A team of explorers made the thrilling rediscovery on a biodiversity survey of Makira Forest in northeastern Madagascar in September 2023. It turns out Spirostreptus sculptus has been hidden in its rainforest home all along, probably known to the local people who live nearby.

The expedition team included insect expert Dmitry Telnov, who describes Spirostreptus sculptus as “One of the largest millipedes in the world. The longest female we observed was 27.5 cm long – the length of an adult man’s forearm! This species has a dark brown body with pale legs and antennae. The body consists of about 60 segments with hundreds of legs.”

Millipedes matter, as Dmitry notes: “Millipedes feed on decayed vegetation (fallen leaves, rotten fruits), fungi, and sometimes animal poop. Their role in nutrient circulation in a forest ecosystem is therefore important.”

Dmitry and the team were surveying the Makira forest in search of other species when they unexpectedly stumbled upon the millipede.

“We found Spirostreptus sculptus in an undisturbed and very wet closed canopy rainforest, in a river valley that was damp and dark. Millipedes are usually quite fragile to drying out and tend to avoid sunny open areas. The forest is quiet in the daytime but full of bird, frog, and cicada sounds in the evening and early morning. The forest is also rich in dead wood (fallen trunks) and millipedes usually hide under trunks or stones during the hot midday.”

Dmitry notes that the forest where Spirostreptus sculptus lives is endangered. The forest is being cut down and becoming isolated from other nearby patches of forest. This could be a problem for slow-crawling species like millipedes, which can’t move easily between forest patches in search of food and mates.

When asked how a giant millipede could go missing for decades, Dmitry explained to Mongabay Kids that:

1) The first scientists to see the millipede in 1897 did not record exactly where in Madagascar they found it. Madagascar is roughly the size of the U.S. state of Texas. That is a massive area to search for a millipede, even one the size of a human forearm!

2) This millipede lives in old-growth rainforests that are difficult to get to. It took Dmitry and his team three days of walking through the forest to get to undisturbed habitat where the millipede appeared.

Once they reached the habitat of Spirostreptus sculptus, how hard was it to find this species that had been hidden for over 120 years? Not that hard, it turns out! “The species appeared itself. There was no need to search for it. Specimens came to our basecamp,” says Dmitry.

The trick to finding the millipede was locating the right habitat in the right part of the large island of Madagascar. And that is how the mystery of the missing giant millipede was solved.

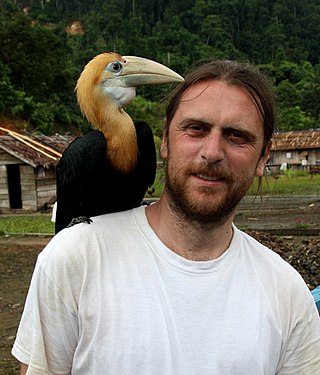

Meet Dmitry!

Dmitry Telnov is an entomologist, biogeographer, and conservationist. He is an expert on the taxonomy of beetles and has discovered many new species during his global expeditions.

Dmitry Telnov. Image: Anthicus, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The expedition described in this story was part of Re:wild’s Search for Lost Species. It also included teams from Antananarivo University, American Bird Conservancy, The Peregrine Fund, Wildlife Conservation Society and the Biodiversity Inventory for Conservation (BINCO), as well as local guides. Altogether, the expedition found 21 species that had not been recorded by science in a decade or more, including fish, beetles, and spiders.

Do you want to look for missing species that nobody has seen for a long time?

As an expert in these matters, Dmitry has some advice for how you could get started. He says:

“In nearly every county or town there are locally threatened or “lost” species of plants, animals, or fungi. You can get more information at your local nature conservation office. Learn what these species look like, where they live, and what they feed on. Try to find potentially suitable habitats or areas for these species in your area, and visit them at periods when the species of your interest is supposed to be active. You may observe it one day! If so, please report your observation to your local nature conservation office.”