Doug Beetle chats with:

Lawyer

Tanya Sanerib

Supplied: Tanya Sanerib

Tanya Sanerib is a Senior Attorney and International Legal Director at the Center for Biological Diversity. Tanya works to protect imperiled species and biological diversity worldwide.

Read how Tanya is working to protect giraffes

Doug Beetle: Could you please explain to us briefly how the Endangered Species Act helps protect plants and animals?

Tanya: Our Endangered Species Act is one of the strongest laws in the world for protecting wildlife. It does that by making certain things that people typically do to plants and animals illegal – sort of like rules at school about not hitting other students or taking someone else’s lunch. But this law protects wildlife.

Animals and plants get these protections – from being hurt or traded or sold – and those protections or rules help them survive.

But the Endangered Species Act listings also helps make sure that needy animals and plants get funding that pays for conservation work and scientific research.

And the listing process can raise attention about species. Almost everyone loves giraffes, but very few people realized that there are fewer giraffes in Africa than there are elephants.

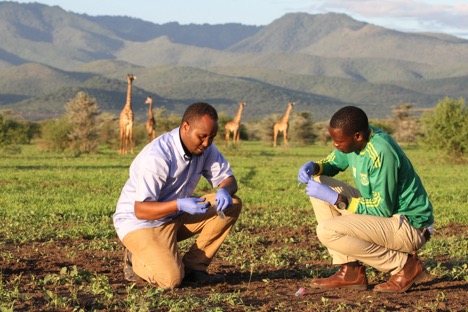

Image supplied: Tanya Sanerib

Doug Beetle: Why did you decide that giraffes should be listed under the Endangered Species Act? What protection would being listed as a legally endangered species give them that they would not have otherwise?

Tanya: Giraffes have been suffering a silent extinction – not many people were aware of their decreasing numbers and the threats they face. But there’s another really important reason why I came to believe that our laws in the United States should protect giraffes.

What really worried me is that some people here are buying a lot of stuff that’s made from giraffes. People in the United States buy all sorts of weird things, including lots of things made with giraffe bones and giraffe skins. It’s gross when you think about it – a pen made out of a dead animal’s bones or a pillow made out of its skin – but a lot of people don’t think about it. And there’s where the Endangered Species Act can really help giraffes. Not only can it stop people from buying all those weird things made with giraffe parts but it can also help them understand why they shouldn’t. Hopefully they’ll learn that having that pen or pillow isn’t worth it when compared to the beauty of a living giraffe and the important role a giraffe plays socially and for its environment.

Add to that the boost that Endangered Species Act protection gives to conservation funding and scientific research. Maybe we’ll even learn why giraffes hum at night.

Doug Beetle: How do you get giraffes listed as an endangered species? Does it take a long time? What are some of the possible problems that could happen and prevent giraffes from being listed as endangered species?

Tanya: What’s really cool about our Endangered Species Act is that anyone can ask to have a species protected. You do that through a document called a petition – and yes, there are a bunch of requirements you have to meet. But it’s a really special request we get to make of our government.

Unfortunately, it usually takes a while for species like the giraffe to get listed. It’s not supposed to take as long as it does, though. The government has deadlines they are supposed to follow to help make sure that animals and plants get protections when they need them. Sadly, the government doesn’t usually do things on time.

But we can go to court and ask a judge to make the government get the job done on time. And we did that to make sure the government makes a decision for giraffes.

Problems can stop this process. For instance, you might ask for a species to be protected but don’t give the government a good reason. Or there might not be enough scientific information on the species. Sometimes we just don’t know that much about a plant or animal. If we can’t tell if the species’ population is getting smaller or one or more things is threatening the species, then it’s hard to protect it. I’m not too worried about that for giraffes, but it can happen. Sometimes politics can influence decisions too, even though they are supposed to be based upon science.

Sadly, some species have waited so long for protection that they went extinct – they disappeared forever – before we could save them. But sometimes other laws or people can help save the animal or plant and then it might not need to be listed.

Image supplied: Tanya Sanerib

Doug Beetle: How did you become interested in being a lawyer that helps endangered species? What were the steps that you took to become a lawyer once you knew that was what you wanted to do?

Tanya: I wanted to be a scientist originally. First a marine biologist, then an ecologist and then a wildlife biologist. And there were two main things that made me decide to be a lawyer for wildlife instead. One, there’s way less math in law than there is in science. Two, I wanted to speak for wildlife. Sometimes scientists get pressure to not get emotionally involved. I think that’s changing now, but over 20 years ago when I decided to go to law school that wasn’t the case. I was worried we were losing animals and plants and I wanted to stop that from happening. I decided that being lawyer and using science to advocate for wildlife would be the best way to help fight extinction.

Doug Beetle: What advice do you have for young people who are interested in laws that help protect endangered species or other parts of the environment and might want to work as a lawyer when they grow up?

Tanya:

Do it! We need all your creative minds to help save the earth. Keep your curiosity, and study science and writing – all those things will help you protect wildlife or the environment or whatever you want to fight for in the natural world.

I get to work with some of the best and most inspiring people and I love what I do. Not everyone can say that about their work! Yeah, it’s hard sometimes, but it’s really rewarding too. And I get to speak for some of the most amazing animals on the planet – like giraffes.