Doug Beetle chats with:

Scientist

Mariella Superina

Mariella Superina with a northern long-nosed armadillo in Colombia. Credit: Programa de Manejo y Conservación de los Armadillos de los Llanos.

Dr Mariella Superina (Dr.med.vet., Ph.D.) is an armadillo scientist and conservationist. Mariella is Chair of the IUCN/SSC Anteater, Sloth and Armadillo Specialist Group, a Research Scientist at CONICET, and Associate Researcher at Fundación Omacha.

Dr Mariella tells us about the fascinating world of armadillos!

This video shows a pichi sand bathing to cool down. Credit: Mariella Superina

Doug Beetle: How did you become interested in armadillos? What scientific questions did you want to answer about them?

Mariella: I grew up in Switzerland, where there are no armadillos because they only live in the Americas. While working on a farm in Brazil, I saw an armadillo and was blown away. I had never seen anything like this before, I didn’t even know such amazing animals existed!

So, when I returned to Switzerland, I started looking for information on armadillos and I realized that not much was known about them. This sparked my interest in armadillos even more. When I was offered the opportunity to write my doctoral thesis on these amazing creatures, I didn’t hesitate a second.

I started compiling all the existing literature on the biology of armadillos and analyzed how they are kept at different zoological institutions. I enrolled in a PhD program in Conservation Biology at University of New Orleans. For my dissertation research I studied pichis, a small armadillo species that only lives in arid and semi-arid regions of Argentina and Chile.

Basically, I wanted to find out as much as I could to save it from extinction. I studied what it eats, where it lives, how many offspring it has, how it copes with the harsh winter, and the diseases that may be affecting it. I also gave talks to raise awareness about pichis and worked with the authorities to protect the species.

I started working with armadillos over 20 years ago, and I’m still fascinated by them!

Doug Beetle: How do you answer your research questions? And what interesting things have you learned about armadillos?

Mariella: We (doing research is always teamwork!) spent many, many hours in the field looking for armadillos.We did this by walking through areas we knew were inhabited by armadillos (because we saw their burrows), on horseback, and mainly in our truck.

When we would see an armadillo, we would run it down and capture it by hand – you have to be quick because once it reaches its burrow, you won’t be able to get it out of there! They’re amazingly fast diggers!

We would then collect all the information we could – measure and weigh them, take blood samples, take pictures to identify them (so that we’d know if we captured the same animal again at another moment), describe where we found it – and then release it again exactly where we had caught it.

Still, there were many questions we could not answer because armadillos spend a lot of time inside their burrows. Sometimes we would drive around for days without seeing a single armadillo, and we were wondering what the reason was.

So, we decided to keep some pichis in large enclosures, where we could study some aspects of their life. We received pichis that had been confiscated by the environmental authorities, rehabilitated them, and then kept them under controlled conditions (of course, we had all the permits to do that, you can’t just keep armadillos as pets).

This allowed us to study when they breed (only in spring) and how many offspring they have (1-2). We also found out that the newborns do not leave the burrow until they are weaned after 40 days, and that they grow amazingly fast. When they first leave the burrow and already eat some solid food, they’re half the size of their mother!

We also investigated why we didn’t see pichis in the field during some months of the year. It turns out they hibernate during winter! For three months, they rarely leave their burrows to save energy. They also enter torpor, which is a short version of hibernation, during periods of environmental stress.

This means that if it doesn’t rain for many months and food is not easily available, pichis will just stay inside their burrows to save energy. This was a fundamental piece of information to understand how they cope with adverse environmental conditions.

But as always in science, every bit of information I collected about armadillos sparked another question I wanted to investigate. For the last 8 years, I have been collaborating with an amazing research and conservation program in Colombia, in northern South America, which allowed me to work with other armadillo species.

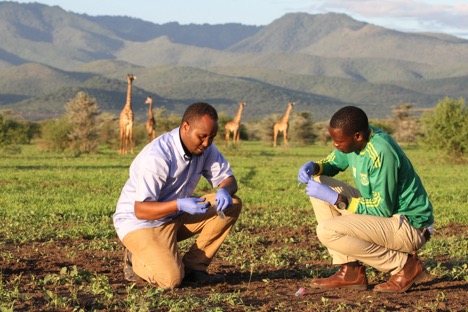

Just last month, our team went to the field in the Orinoco region of eastern Colombia to catch northern long-nosed armadillos (they look like nine-banded armadillos, but are smaller). That was quite a challenge because they live in the savanna, where the grass can be up to a meter high – try walking in that high grass and spot an armadillo that weighs less than 2 kg!

We managed to capture a few armadillos and equipped them with radio transmitters, which now allows us to monitor their movements. This will help us understand how much they move per day and if they always stay in the grasslands or also use plantations or forest patches.

Doug Beetle: What other armadillo mysteries would you like to solve?

Mariella: Oh, there are so many mysteries about armadillos that I would like to solve! For instance, we still don’t know how many armadillos are out there. It’s very difficult to determine how many armadillos live in an area because they spend so much time inside their burrows.

Also, we know that a female pichi gives birth to 1-2 offspring per year, but we don’t know how many of them survive until adulthood. And we don’t even know how long armadillos live!

Then, there are other armadillos of which we know virtually nothing, such as the pink fairy armadillo, a tiny armadillo that lives underground and fits in the palm of my hand – it’s an exciting challenge to try to find out more about how and where it lives!

Doug Beetle: What conservation challenges are armadillos facing in the wild? And what can young people do to help conserve armadillos?

Mariella: Armadillos are hunted in all the countries where they naturally occur. They are also victims of road traffic, killed by dogs and, especially, affected by habitat loss and fragmentation.

Although some armadillo species thrive in modified habitats, such as agricultural plantations, most of them do not. As their diet mainly consists of insects (although some armadillo species also eat plant matter, lizards, small rodents, scorpions, spiders, and even carrion), they are probably also affected by insecticide spraying, as this kills their main food source.

Finally, climate change may be another challenge for armadillos, as they are sensitive to changes in environmental temperature and rainfall.

What can young people do to help conserve them? As my friend Tinka Plese from Fundación Aiunau in Colombia always says: Keep them in your heart, but leave them in the wild.

Do not keep armadillos (or any other wild animal) as pets, they won’t be happy. Instead, if you see a wild armadillo, enjoy watching this unusual and fascinating animal!